|

| https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/36320/Maryland1906m.jpg?sequence=1 |

Little is known about the slaves owned by the Dimmitt / Demmett's in Maryland, other than the likely assumption that it was prominent. William Dimmitt owned significant amounts of land, as did his children. With labor-intensive crops, such as tobacco, slavery is simply assumed.

The following sources were discovered in 2014, while at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' genealogical library in Salt Lake city Utah.

From the Baltimore County Maryland Deeds Records

"1 Aug 1765, came Charles Walker, clerk and storekeeper to William Lux, merchant, of Baltimore Co., Maryland stated that James Demmett has run away to Carolina and is in debt to said William Lux, the said William being gone to Norfolk, Virginia, this disponet employed Nicholas Gardner to go with him in quest of said James Demmett and they over took him in Leesburg, Virginia and said James gave them the negro man Jack and negro woman Judy, for debt. Signed Charles Walker and Nicholas Gardner. Wit: Benjamin Rogers"

p. 339

"2 Jun 1742, Jacob Bull, of Baltimore Co., Maryland to his son-in-law William Dimmitt Jr, of same, for love and affection, the negro boy, age about 14 years, called Shrowbury. Signed Jacob Bull. Wit: William Young and Darby Hornby."

p. 143

Update

On June 20, 2020, while searching databases, the following article came to light. This article illuminates the name of another woman "owned" by the Dimmitt family in Maryland. Her name was "EASTER." I'm glad to present her name to the world.

Unfortunately, Easter was recaptured by her slave owner Moses Dimmitt.

|

Federal Gazette & BALTIMORE Daily ADVERTISER.

Monday, Jul 07, 1800

Baltimore, MD

Vol:XIII Issue:2064

Page:4 |

Whatever Easter's fate, I hope her life and her descendants found peace, and were blessed.

On September 13, 2020, while researching the work of Dr. Richard Miller on the Dimmitt line, it was found in a land deed involving the Sheriff of Baltimore Maryland and Rachel Dimmitt, another associate of Jack, who had been a slave of James Demmett, was identified as "Jim."

It is an honor to remember Jim to the world.

May he rest eternally in the arms of the Lord. May Jim's descendants find peace in this world and the next.

Baltimore Maryland

Elisha Dimmitt <1840 US Federal Census

24-35

|

Male

|

|

>10

|

Female

|

|

>10

|

Female

|

|

24-35

|

Female

|

William Demmitt <1830 US Federal Census>

>10

|

Male

|

|

>10

|

Male

|

|

>10

|

Male

|

|

10-23

|

Male

|

|

36-54

|

Male

|

|

36-54

|

Male

|

William Dimmett <1840 US Federal Census

>10

|

Male

|

|

>10

|

Male

|

|

10-23

|

Male

|

|

24-35

|

Male

|

|

55-99

|

Male

|

|

24-35

|

Female

|

|

24-35

|

Female

|

Frederick, Maryland

Henry Demmitt

>10

|

Female

|

Henry Demet <1860 US Federal Census>

12

|

Male

|

"Mulatto"

|

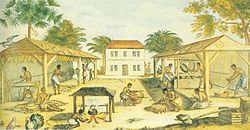

Emergence of a slave economy (1670s to 1730s)[edit]

In the period following Oliver Cromwell's fall in England, the colony grew and transitioned to a slave economy. It saw the beginnings of industry and urbanization.

At the turn of the eighteenth century, King William's War (1689-1697) and Queen Anne's War (1702-1714) brought Maryland into depression again as European demand for tobacco decreased sharply. As a result, many poorer farmers began to diversify their efforts, adding cattle and grain to their fields and adopting crafts.[15] And despite the economic uncertainty, indentured servants arrived in large numbers until the end of the seventeenth century. With the dawn of the 1700s, however, farmers shifted to slave labor for their fields.[16] Between 1704 and 1720, the slave population shot from 4,475 to 25,000.[17]

During this period, the slave population was increasingly concentrated in estates with more than ten slaves.[18][19] Some historians consider this transition to a slave economy to be the start of greater social stratification in the colony, as wealthier Marylanders were then able to increase their farms' productivity through the increasing returns to scale that slave labor enabled.[17]According to historian Trevor Burnard, the wealthiest farmers in the colony held 36 percent of the wealth prior to 1708. By 1742, they held 58 percent.[20]

Other changes were afoot, too. In the 1730s, farmers began to smelt iron near Annapolis.[21] In Annapolis itself, then the largest city in the colony, the urban population doubled between 1715 and 1740.[22] In this era of transition, the colony again fell into economic depression in the 1730s.[23]

History of slavery in Maryland

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The institution of slavery in Maryland would last around 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans to brought to St. Mary's City, Maryland to the final elimination of slavery in 1864 during the penultimate year of the American Civil War.

Initially, slavery developed along very similar lines to neighboring Virginia. The early settlements and population centers of the Province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay and, as in Virginia, Maryland's economy quickly became centered on the farming of tobacco for sale in Europe. Tobacco demanded cheap labor to harvest and process the crop, the more so as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became ever larger and more efficient. At first, emigrants from England in the form of indentured servants supplied much of the necessary labor but, as Englishmen found better opportunities at home, the forcible immigration and enslavement of Africans began to supply the bulk of the labor force.

By the 18th century Maryland had developed into a plantation colony, requiring vast numbers of field hands. In 1700 the Province had a population of about 25,000, and by 1750 that number had grown more than 5 times to 130,000. By 1755, about 40% of Maryland's population was black.[1] An extensive system of rivers facilitated the movement of produce from inland plantations to the Atlantic coast for export. Baltimore was the second-most important port in the eighteenth-century South, after Charleston, South Carolina.

During the American Civil War, fought in part over the issue of slavery, Maryland remained in the Union, though many of her citizens (and virtually all of her slaveholders) held strong sympathies towards the rebel Confederate States. Maryland, as a Union border state, was not included in President Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, which declared all slaves in Southern Confederate states to be free. Slavery would hang on in Maryland until the following year, when a constitutional convention was held which culminated in the passage of a new state constitution on November 1, 1864. Article 24 of that document at last outlawed the practice of slavery. The right to vote was extended to non-white males in the Maryland Constitution of 1867, which remains in effect today.

Beginnings[edit]

Tobacco[edit]

Main article: Tobacco in the American Colonies

From the beginning, tobacco was the dominant cash crop in Maryland. Such was the importance of tobacco that, in the absence of sufficient silver coins, it served as the chief medium of exchange. John Ogilby wrote in his 1670 book America: Being an Accurate Description of the New World: "The general way of traffick and commerce there is chiefly by Barter, or exchange of one commodity for another".[2]

Since land was plentiful, and the demand for tobacco was growing, labor tended to be in short supply, especially at harvest time. The first Africans to be brought to English North America landed in Virginia in 1619. These individuals appear to have been treated as indentured servants, and a significant number of African slaves even won their freedom through fulfilling a work contract or for converting to Christianity.[3]

Some successful free people of color, such as Anthony Johnson, acquired slaves or indentured servants themselves. This evidence suggests that racial attitudes were much more flexible in the colonies in the 17th century than they would subsequently become.[4]

Import of African slaves[edit]

The first Africans were brought to Maryland in 1642, when 13 slaves arrived at St. Mary's City, the first English settlement in the Province.[5] However, their legal status was initially unclear and colonial courts tended to rule that a slave who accepted Christian baptism should be freed. In order to protect the rights of their owners, laws began to be passed to clarify the legal position.[5]

In 1661 the Maryland Assembly passed a law explicitly forbidding "miscegenation", that is to say marriage between different races.[6] Three years later, in 1664, under the governorship of Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore, the Assembly ruled that all slaves should be slaves for life, and that the children of slaves should also be enslaved for life. The 1664 Act read as follows:

- Be it enacted by the Right Honorable, the Lord Proprietary, by the advice and consent of the Upper and Lower House of this present General Assembly, that all negroes or other slaves already within the Province, and all negroes and other slaves to be hereafter imported into the Province shall serve durante vita. And all children born of any negro or other slave shall be slaves as their fathers were for the term of their lives."[5][7][8]

In this way the institution of slavery in Maryland would become indefinitely self-perpetuating, and the numbers of slaves in Maryland would grow inexorably until the institution's final eradication, 200 years later, during the American Civil War.

The wording of the 1664 Act suggests that Africans may not have been the only slaves in Maryland. Although there is no direct evidence of the enslavement of Native Americans, the reference to "negroes and other slaves" may imply that, as in Massachusetts, local Indians may have been enslaved by the colonists.[9] Alternatively, the wording in the Act may have been intended to apply to slaves of African origin but of mixed-race ancestry. An early consequence of this law was the enslavement of Nell Butler, an Irish-born indentured servant to Lord Calvert, who chose to marry a slave.

Further legislation would follow, entrenching and deepening the institution of slavery. In 1671 the Assembly passed an Act stating expressly that baptism of a slave would not lead to freedom. The Act was apparently intended to save the souls of the enslaved; such that no slave owner should be discouraged from baptizing his human property for fear of losing it.[9] In practice, such laws permitted both Christianity and slavery to develop hand in hand.

However, at this early stage in Maryland history slaves were not especially numerous in the Province, being greatly outnumbered by indentured servants from England. the full impact of such harsh slave laws would not be felt until large scale importation of Africans began in earnest in the 1690s.[5] During the second half of the 17th century, the British economy gradually improved and the supply of British indentured servants declined, as poor Britons had better economic opportunities at home. At the same time, Bacon's Rebellion of 1676 led planters to worry about the prospective dangers of creating a large class of restless, landless, and relatively poor white men (most of them former indentured servants). Wealthy Virginia and Maryland planters began to buy slaves in preference to indentured servants during the 1660s and 1670s, and poorer planters followed suit by c.1700. Slaves cost more than servants, so initially only the wealthy could invest in slaves. By the end of the seventeenth century, planters shifted away from indentured servants, and in favor of the importation of African slaves.

No comments:

Post a Comment